What will citizens of the 22nd century see as the great art of the 20th? I think it will mostly be movies.

Casablanca, Satjit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, Charlie Chaplin’s movies, The Imitation Game, Sophie’s Choice, the “Colors of the Wind” sequence from Pocahontas, the ravishing “Ebben? . . . Ne andro lontana” aria from Diva. They will recognize the value of such novels and plays as Lolita; I, Claudius; The Caucasian Chalk Circle; The Crucible. But it will be thought of as a very sad time for separate, standalone works of visual art, music, and poetry. We look for art which expresses genuine feeling . . .

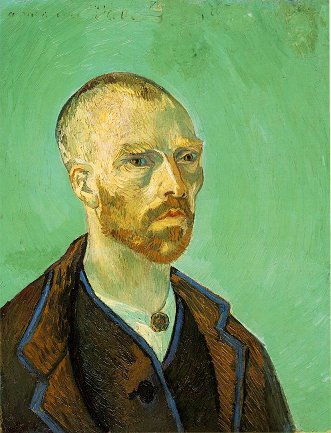

Not only have visual artists abandoned the subject (other human beings) which most moves us, but the works they have created only remotely resemble anything we actually see. They fail to move us because (1) the artist didn’t feel anything and doesn’t intend for us to feel anything; they are intended to be merely “interesting” or (2) the artist felt something, but is speaking in a made-up language which only he and other aficionados can understand. He has abandoned the shared experience in which all great art is grounded.

Composers of 20th century music abandoned the language which Western music had spoken for centuries. They created an atonal, frequently arrhythmic, music with elements from a variety of non-Western music, but mostly just made up. Unfortunately, even the greatest of its practitioners (Stravinsky, for instance), though they shouted and banged and whispered superbly, have failed to move us. They are talking in Esperanto, a language which we understand only with difficulty, and which its speakers find impossible to speak movingly, even to themselves.*** (Note: We speak here of “classical” music. It could well be that 20th and 21st century popular music is what will be remembered, loved, and studied.)

Twentieth-century poetry got started more slowly in its decline. Yeats, Millay, Auden, and Dylan Thomas were writing coherently, meaningfully, saying things right up to mid-century. But the opposing forces of obscurity, abstraction, and inconsequentiality (Pound, Stevens, William Carlos Williams) eventually won out. Pound and Frost championed the “sound of speech”, but it was a very pedestrian speech, speech which failed to move us. And then the sound of poems was overshadowed entirely by poetry as written image. Perversely, as visual art abandoned its natural role as the presentor of reality-grounded images, poetry abandoned its own natural role as the medium of beautiful/forceful speech and became the new, crippled, presentor of images. (Images have always played an important role in poetry — but as tools, not as ends in themselves.) Our real criticism of 20th century poetry, however, is not its emphasis of image over sound, but rather its failure to address what’s really important to human beings. How many poems these days deal with the deep emotions which death, love, loss of love, eternity evoke in us? Poetry as a means of expressing real feelings in a “bold and nervous lofty language” (Melville) has been lost.

The experience of the art community with Impressionism, proper and Post-, seeing artists who had been rejected and ridiculed by their own generation deified by succeeding ones, seemed to teach a lesson: new is good; different is good; existing standards/aesthetics don’t apply. But Impressionist art, though radically different in its form, was grounded in real, recognizable objects: people, trees, stars. We should have learned the lesson, “Don’t judge a book by its cover”; instead we learned “Don’t judge a book which is radically different”.

The current Art community exists as small, self-congratulatory circles of artists, poets, composers reinforcing each other’s empty creations. The vast majority of cultured people continue to look to previous centuries for artistic sustenance. (And, in fairness, fail to produce any new art themselves.) Will this change? Will cultured people in the 21st century be passionate in large numbers for the works of Jackson Pollack, John Cage, and William Carlos Williams? Not likely. So what will happen? At some point, the 20th century — especially the last half of the 20th century and the early 21st — will be recognized as the wasteland that it is and young artists will turn to the reservoir of older, greater Western art for inspiration.

The “Casablanca” chapter of Genius Ignored ends with this:

We live in a gray, uncertain time. We question whether life is really important. Meaningful relationships seem impossible…. Casablanca is a letter from the past. It says that life is extremely important. And that not only is love possible, it can reach to the very deepest parts of our being. And how we live (in freedom and under the rule of just law) is so important that noble people will willingly sacrifice even such deep love for it…. In the darkest hours of World War II, on a Warner Bros.’ studio backlot, a hundred people got together to act out and record what promised to be a fairly standard entertainment of love and intrigue. Somehow, what resulted was much more: a rich, supremely life-affirming fable of duty and love….

Do you know of other art –especially contemporary art available through the Web– which expresses genuine feeling?

Please email Lucius @ jspecht.org

The original Humanists (Giotto, Petrarch, Erasmus) turned away from 13th-century religious abstraction to celebrate the beauty and power of human beings and nature. Artists of coming centuries will, in a similar fashion, turn away from the impotent, Scientific abstractions of the 20th century, returning to an art which expresses genuine feeling and is grounded in genuine culture.

*** This was written before I had heard Morten Lauridsen’s “Lux Aeterna” (1998). That’s an exception: Lauridsen Wikipedia article .

Jan. 23, 2015: Lucius reveals identity: “Lucius Furius Out of Closet”

Created: Aug 17, 1997

Last Updated: Dec. 1, 2018