Summary: Though Nabokov lived to see his work widely- and well-appreciated, he suffered suppression of his books in his native Russia and had tremendous difficulty finding a publisher for his novel, Lolita.

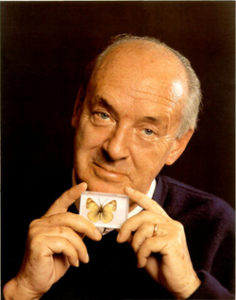

[Photo from 3 Quarks Daily web site]

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov was born into a wealthy, landed family on April 23, 1899, in St. Petersburg, Russia. His father was part of the short-lived, liberal Kerensky government. When the Bolsheviks came into power, the Nabokovs were forced into exile. Vladimir spent the years of 1919-22 studying at Cambridge University in England. On March 28, 1922, while Vladimir was in Berlin (where his family was then residing) on his Easter vacation, extreme Russian rightists/monarchists tried to assassinate Paul Milyukov, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party-in-exile, who was addressing a crowd of 1500 Russian expatriates at the Berlin Philharmonia Hall. Nabokov’s father, who was also on the platform, tried to protect Milyukov and was killed.

Nabokov spent most of his twenties and thirties in Berlin, lived in Paris for two years, and then, in 1940, emigrated to the United States.

Nabokov was very intelligent, had an excellent sense of humor, and created some very original stories and characters. His true genius, however, lay in the realm of language. How improbable that this Russian emigre who had lived in England and America for a total of only 16 years should write a novel whose strength is not its plot, not its ideas, but its beautiful, exuberant English.

Lolita grew out of a 30-page story (written in Russian, containing both the nymphet and the marrying-her-mother idea) which Nabokov had drafted in Paris in late 1939 or early 1940. “I was not pleased with the thing and destroyed it sometime after moving to America in 1940.

. . . The book developed slowly, with many interruptions and asides. . . . I finished copying the thing out in longhand in the spring of 1954 and at once began casting about for a publisher. . . .

Some of the reactions were very amusing: one reader suggested that his firm might consider publication if I turned my Lolita into twelve-year-old lad and had him seduced by Humbert, a farmer, in a barn, amidst gaunt and arid surroundings, all this set forth in short, strong, ‘realistic’ sentences (‘He acts crazy. We all act crazy, I guess. I guess God acts crazy.’ Etc.). . . . Publisher X, whose advisers got so bored with Humbert that they never got beyond page 188, had the naiveté to write me that Part Two was too long. Publisher Y, on the other hand, regretted there were no good people in the book. Publisher Z said if he printed Lolita, he and I would both go to jail.

No writer in a free country should be expected to bother about the exact demarcation between the sensuous and the sensual; this is preposterous; I can only admire but cannot emulate the accuracy of judgment of those who pose the fair young mammals photographed in magazines where the general neckline is just low enough to provoke a past master’s chuckle and just high enough not to make a postmaster frown. I presume there exist readers who find titillating the display of mural words in those hopelessly banal and enormous novels which are typed out by the thumbs of tense mediocrities and called ‘powerful’ and ‘stark’ by the reviewing hack. There are gentle souls who would pronounce Lolita meaningless because it does not teach them anything. I am neither a reader nor a writer of didactic fiction, and, despite John Ray’s assertion, Lolita has no moral in tow. For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm. . . .

. . . My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody’s concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English, devoid of any of those apparatuses — the baffling mirror, the black velvet backdrop, the implied associations and traditions — which the native illusionist, frac-tails flying, can magically use to transcend the heritage in his own way.” (from the “afterword” to Lolita, “Vladimir Nabokov on a book entitled LOLITA”)

The unpublished manuscript was read by a variety of literary figures. Novelist Mary McCarthy’s reaction was “negative and perplexed”. Critic Edmund Wilson liked it “less than anything else of yours I have read”. Philip Rahv, editor of Partisan Review, thought it “charming”. [Boyd, p. 264]

Despairing of finding an American publisher, Nabokov sent the book to friends in Europe. When Maurice Girodias/Olympia Press expressed an interest, Nabokov was elated. He knew that they had published James Joyce and Henry Miller; he did not know that the bulk of their recent publications had been pornographic novels along the lines of Until She Screams and How to Do It.

Girodias published the book in August, 1955. Graham Greene named it one of the three best books of 1955 in the Christmas issue of the London Sunday Times. A number of false starts ensued, but the book gradually gained momentum and, despite all the fears to the contrary, was never actually banned or censored in the United States.

Lolita is about passion/obsession. A passion beyond the limits of acceptability, a passion whose price is exile from society; extreme, unadulterated, insane passion. “Humbert” is an artist (the creator of this narrative) and there’s a sense in which this book is not just about the narrator’s passion for Lolita but also the passion of the artist for his art.

Nabokov is a master of words. Their nuances, their interminglings:

This then is my story. I have reread it. It has bits of marrow sticking to it, and blood, and beautiful bright-green flies. At this or that twist of it, I feel my slippery self eluding me, gliding into deeper and darker waters than I care to probe. . . .

Publishers W, X, Y, and Z had failed to recognize the novel’s greatness.

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet. . . .

[from W.H. Auden’s, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”]

Nabokov went on to write a number of other novels (the most brilliant being Pale Fire) and to translate most of his earlier novels from Russian into English. In 1961 he and his wife moved to Switzerland. He died on July 2, 1977, at the age of 78.

References

Nabokov on the Web

- Zembla (U.C.–Santa Barbara) [Links to Penn State not working, Mar. 1, 2023]

- The Nabokovian, the International Vladimir Nabokov Society

- Wikipedia

- The Online Literary Criticism Collection page for Nabokov … with several additional links.

- Lolita at 50; The Disgusting Brilliance of Lolita

- Fascinating Canadian Broadcasting Company (1958) two-part (5 minutes each) discussion of Lolita by Nabokov, Lionel Trilling, and the CBC’s Pierre Berton: part 1 ; part 2

- 58-minute Nabokov: My most difficult book youtube. From a 1989 VHS. “The story of how the great Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov conceived and created his masterpiece ‘Lolita’, told in his own words and those of Antonia Byatt, Martin Amis, Edmund White, his son Dmitri Nabokov and biographer and critic Brian Boyd. Also Maurice Girodias, Olympia.” The interviews are interesting, but I found the (extensive) reading from the text – emphasizing overtly sexual passages – less so.

- Though the above are the two best that I found, many other youtube videos are retrieved by the search (in youtube) of nabokov and lolita .

Do you know of art –especially contemporary art available through the Web– which expresses genuine feeling? Please email me: Lucius @ jspecht.org

link corrected, 2011

one link and two youtube videos added, 2017