The path by which I arrived at Robert Graves’ The White Goddess is interesting: A visitor to my website recommended John Montague’s poetry, especially his collection, A Rough Field. My library didn’t have that one but did have another: About Love. I liked a number of the poems and was especially taken by his translation of Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill’s “Blodewedd”. I was curious about the title. One of the hits I found for “Blodewedd” on the Web described her as the White Goddess, subject of Robert Graves’ book by the same title. I was vaguely aware of this book but had never read it.

I found the Foreword and parts of the first chapter entrancing but was disappointed by what followed (too esoteric, too complicated). I was about to give up when I arrived at Chapter 22 (“The Triple Muse”) where the promise of the Foreword began to be fulfilled.

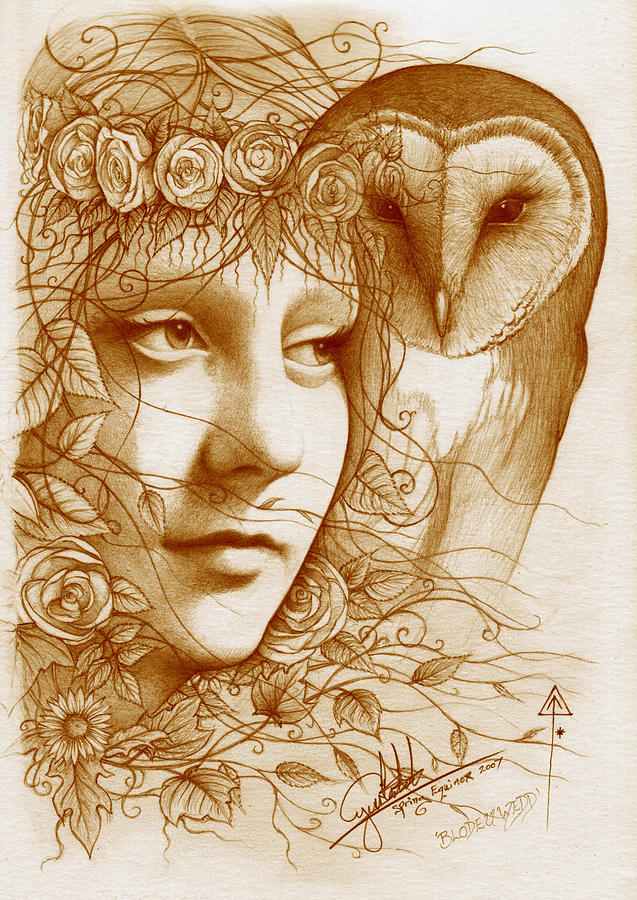

Graves’ thesis is just as startling and bold and bald today as it (no doubt) was in 1948: “…a true poem is necessarily an invocation of the White Goddess, or Muse, the Mother of All Living, the ancient power of fright and lust…. [p. 10] …The function of poetry is religious invocation of the Muse; its use is the experience of mixed exaltation and horror that her presence excites. [p. xii] [Note: the page references are to the 1948 edition.]Blodeuwedd drawing by Yuri Leitch

My thesis is that the language of poetic myth anciently current in the Mediterranean and Northern Europe was a magical language bound up with popular religious ceremonies in honour of the Moon-goddess, or Muse, some of them dating from the Old Stone Age, and that this remains the language of true poetry… [p. x]

My thesis is that the language of poetic myth anciently current in the Mediterranean and Northern Europe was a magical language bound up with popular religious ceremonies in honour of the Moon-goddess, or Muse, some of them dating from the Old Stone Age, and that this remains the language of true poetry… [p. x] The Goddess is a lovely, slender woman with a hooked nose, deathly pale face, lips red as rowan-berries, startlingly blue eyes and long fair hair; she will suddenly transform herself into sow, mare, bitch, vixen, she-ass, weasel, serpent, owl, she-wolf, tigress, mermaid, or loathsome hag…. I cannot think of any true poet from Homer onwards who has not independently recorded his experience of her. The test of a poet’s vision, one might say, is the accuracy of his portrayal of the White Goddess and the island over which she rules. The reason why the hairs stand on end, the skin crawls and a shiver runs down the spine when one writes or reads a true poem is the a true poem is necessarily an invocation of the White Goddess, or Muse, the Mother of All Living, the ancient power of fright and lust–the female spider or the queen-bee whose embrace is death. [p. 10]

… As Goddess of the Underworld she was concerned with Birth, Procreation, and Death. As Goddess of the Earth she was concerned with the three seasons of Spring, Summer, and Winter: She animated trees and plants and ruled all living creatures. As Goddess of the Sky she was the Moon, in her three phases of New Moon, Full Moon, and Waning Moon. This explains why from a triad she was so often enlarged to an ennead. But it must never be forgotten that the Triple Goddess, as worshipped for example at Stymphalus, was a personification of primitive woman–woman the creatress and destructress. As the New Moon or Spring she was girl; as the Full Moon or Summer she was woman; as the Old Moon or Winter she was hag. [pp. 319-20]

The third stage of cultural development–the purely patriarchal, in which there are no Goddesses at all–is that of later Judaism, Judaic Christianity, Mahomendanism and Protestant Christianity…. [p. 322]

…The whiteness of the Goddess has always been an ambivalent concept. In one sense it is the pleasant whiteness of pearl-barley, or a woman’s body, or milk, or unsmutched snow; in another it is the horrifying whiteness of a corpse, or a spectre, or leprosy…. [p. 361]

…For [the poet] there is no other woman but Cerridwen and he desires one thing above all else in the world: her love. As Blodeuwedd, she will gladly give him her love, but at only one price: his life. She will exact payment punctually and bloodily. Other women, other goddesses, are kinder-seeming. They sell their love at a reasonable rate–sometimes a man may even have it for the asking. But not Cerridwen: for with her love goes wisdom….

Cerridwen abides. Poetry began in the matriarchal age, and derives its magic from the moon, not from the sun. No poet can hope to understand the nature of poetry unless he has had a vision of the Naked King crucified to the lopped oak, and watched the dancers, red-eyed from the acrid smoke of the sacrificial fires, stamping out the measure of the dance, their bodies bent uncouthly forward, with a monotonous chant of “Kill! kill! kill!” and “Blood! blood! blood!” [p. 372-3]

…Now the Jews are fast turning “liberal” and both they and the Christians are further away than they ever were from the ascetic holiness to which Ezekiel and his Essene successors hoped to draw the world, and after many theological ups and downs we have come to be governed by the unholy triumvirate of Pluto god of wealth, Apollo god of science and Mercury god of thieves….Unless the ascetic Michael can quickly reorganize his scattered legions of angels for a new puritannical campaign of sexless unworldliness, there can be no escape from the present more than usually miserable state of the world until a new Battle of the Trees is fought: “A renewal of conflict / Such as Gwydion made,…” and the supreme Godhead thereby redefined; until the repressed desire of the Western races, which is for some practical form of Goddess worship, with her love not limited to maternal benevolence and her afterworld not deprived of a Sea, finds satisfaction at last…. [pp. 390-1]

…The function of poetry is religious invocation of the Muse; its use is the experience of mixed exaltation and horror that her presence excites…. This was once a warning to man that he must keep in harmony with the family of living creatures among which he was born, by obedience to the wishes of the lady of the house; it is now a reminder that he has disregarded the warning, turned the house upside down by capricious experiments in philosophy, science, and industry, and brought ruin on himself and his family. “Nowadays” is a civilization in which the prime emblems of poetry are dishonoured. In which serpent, lion, and eagle belong to the circus-tent; ox, salmon and boar to the cannery, racehorse and greyhound to the betting ring; and the sacred grove to the saw-mill. In which the Moon is despised as a burned-out satellite of the Earth and woman reckoned as “auxiliary State personnel.” In which money will buy almost anything but truth, and almost anyone but the truth-possessed poet. [p. xii]

These ideas really hit home since they name, give a coherence to, the most important feelings in my own poems:

energy, grace, composure, and sensitivity

are blended in such a quantity

that they overflow

and color with an exquisite beauty every pore of the body,

fill with a subtle music every gesture, every word….

kittens and toads.

And the strange foods you gave us!…

… but, still, you break our hearts–

like tigers stepping on sparrows’ eggs,

like a deer, walking silently through a strand of spiders’ silk, taut between trees,

you break our hearts.

…all your beauty’s joyous ache…

…We’d tasted love–

sweet, imbalanced, temporary–

now longed for the same only more complete,…

…the life-force running through each living creature,

as straight and true as a ray of light from that galaxy in Andromeda,

willing us to live, grow and be fruitful.

“…Now you must feel the cold truth of my not loving you.”

…women like Ilsa —

so beautiful and passionate

that just the memory of their love, just the shadow,

is enough….

For me, reading it made me understand more clearly [my own extrapolation here] the intertwining of love, death, and posterity: how love’s wild ache, that sickness-unto-death, is a manifestation of the life-force, desire to cheat death, to send our genes shooting through time in the most perfect form possible…

Graves wrote 130 books!

Graves’ thing for the White Goddess was not just talk. He had two wives, but idolized and loved various other women. In his thirties and early forties, he was involved with Laura Riding, a fellow poet and critic; in his fifties and sixties, his “muses” were beautiful, talented, twenty-ish women. There was actual sex in some cases but the main characteristic of these relationships was his idolization, his worship of these women. Usually, he was the one who ended up hurt and foolish-looking:

I, in turn, don’t generally care for Graves’ poetry, finding it unmusical and unmoving. Some exceptions: “The Siren’s Welcome to Cronos” , “Darien”, and the dedication to The White Goddess (1948 edition):

[Note: a different, expanded version of the following poem appears in the Collected Poems as “The White Goddess”. I like the (earlier) one below better. One sample “improvement”: in the later version, the last line, “Careless of where the next bright bolt might fall”, becomes “Heedless of where the next bright bolt might fall.” “Heedless” does not work sound-wise the way “Careless” does (“Careless of where“). “Careless” has a wildness, a recklessness to it. “Careless of” is a much more interesting and original usage….]

Your eyes are flax-flower blue, blood-red your lips,

Your hair curls honey-colored to white hips.

All saints revile you, and all sober men

Ruled by the God Apollo’s golden mean;

Yet for me rises even in November

(Rawest of months) so cruelly new a vision,

Cerridwen, of your beatific love

I forget violence and long betrayal,

Careless of where the next bright bolt might fall.

- robertgraves.org : the best, most comprehensive website; note especially the Online Resources

- 32 of Graves’ poems (selected by Shalizi)

- John Presley’s review of Miranda Seymour’s, Robert Graves: Life on the Edge

- Conversation on Robert Graves, the White Goddess, and related things … “between Mama Rose and Mike Nichols (of The Witches’ Sabbats fame)” —not the movie director

- Wikipedia

Graves in Print

- Graves, Robert. The White Goddess: A historical grammar of poetic myth. Farrar, Straus, and Cudahy, 1948.

- Graves, Robert. Collected Poems. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1958.

- Chapter 3 (“Graves and the White Goddess”) of Randall Jarrell’s, The Third Book of Criticism. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969.

- Chapter 10 (“The Coming of the Goddess”) of Douglas Day’s Swifter Than Reason: The Poetry and Criticism of Robert Graves. University of North Carolina Press, 1963.

Copyright © Lucius Furius 1998; updated:

2009 (links)

2012 (datarealm.com)

2015 (corrected: “The Robert Graves Archive” link and Shalizi link)

2017 (reformatted page)

2017 (changed title of page; link to “Conversation on Robert Graves …”)

2023 (updated link to robertgraves.org)