My name is Toby Hemminger. Below is a transcription of some (rather badly deteriorated) hand-written pages which I found in a chest in my great-aunt’s basement last week. My great-aunt lives in Aldershot (England). They were labelled “Shakespeare Interrogatories” and were written by my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather, Bartholomew Twyne (? – 1615). I’m doing some genealogical research, which is why I was looking through this chest. There are a couple other “interrogatories” involving other people but none nearly so important as Shakespeare…. Please put them on your website if you think they will be of interest to your readers….

Bartholomew Twyne’s “Shakespeare Interrogatories“:

Learning that the poet William Shakespeare, who had for some years been residing in Stratford, was for a time sojourning in London, I arranged to meet him at the Mermaid in Bread Street on the evening of 10 December 1614. I envied the easy, flowing grace with which he wrote. I felt his Genius to be an extraordinary one, most worthy of study, and did purpose to record the events of his life….

Learning that the poet William Shakespeare, who had for some years been residing in Stratford, was for a time sojourning in London, I arranged to meet him at the Mermaid in Bread Street on the evening of 10 December 1614. I envied the easy, flowing grace with which he wrote. I felt his Genius to be an extraordinary one, most worthy of study, and did purpose to record the events of his life….

[After greeting each other and ordering some ale, I questioned him as follows:]

“YHI” = “Your Humble Inquisitor” (Bartholomew Twyne)

“WmS” = William Shakespeare

<YHI:> Pray forgive me, sir, for saying so, but you look pale. Are you not well?

<WmS:> Merely a touch of the ague…. But ’tis true that my three brothers, all of them younger, *have* all gone to the grave these ten years past. Who knows?… You want to record the life and thoughts of William Shakespeare, that men years hence will know who I was….

<YHI:> Yea, by your leave.

<WmS:> I doubt they’ll have an interest….

<YHI:> How likest thou the life of Stratford? Do you not miss London’s sounds, the smells, the fellowship?

<WmS:> I can do without the smells, I’ll warrant you…. I do miss my friends and the theatres. But my family has always lived in Warwickshire. I married there. When I came to London my wife remained at home. And now my children have spread their roots there too.

<YHI:> So you were born in Stratford?

<WmS:> Yes. In 1564. My father was a glover. His father and my mother’s were both yeomen. I had the three brothers, now dead, and a sister, living still in Stratford.

My father was a good man but had not much luck with his glovery. We didn’t starve but accumulated no great riches either. My mother descended of the ancient Arden family. Though she could read but little she was a wondrous inventive and quick speaker — a great lover of words.

I disliked my Latin much less than the average schoolboy, but what truly moved me was the players who visited Stratford –Worcester’s men and Leicester’s– what a glorious world they inhabited. I wrote poems and imagined myself a great actor. And I dreamt of restoring my family, the Shakespeares and the Ardens, to our rightful place of honour in society. In my eighteenth year those dreams came crashing to the ground.

<YHI:> What befell thee?

<WmS:> I became enamoured on a girl of honourable parentage and got her with child. Not a girl, in truth: she was twenty-six. We married. The fruit of that union was our daughter Susanna. And two years after, our twins Hamnet and Judith were born. There was I, an aspiring poet, twenty years old, with a wife and three children. I continued in the work I’d been doing for several years previous, as an usher at the grammar school and as a helper to my father in his glove-making.

But I did not lose my hopes. I read my Ovid with far greater zeal than I had as a schoolboy, and Painter’s translations, Froissart’s Chronicles, everything I could lay my hands on….

Though my father thought it vain and foolhardy, I persuaded my wife and my mother that I should try my fortune as an actor. When the players came to Stratford the year before the Armada I performed for them several parts, a few of which I myself had written. Leicester’s men needed players and we were agreed that I should join them in London. We knew it would be hard for Anne, caring for the children without me, but my parents stood ready to ease that burden.

My twenty-fourth year found me on the stage of the old Theatre in Shoreditch as the mighty Spanish navy sank to the bottom of the English Channel; as Ned Alleyn played the “Spanish Tragedy” and Kit Marlowe wrote his “Tamburlaine”. What a marvellous time to be in London!

In truth, at first I was more of a tinker than an actor: mending broken chairs, stitching a torn curtain, tending the horses…. But when I did well at small parts, they gave me larger. And when they found I could take an awkward or poorly-written line and make it more pleasing to the ear, they quickly gave me more of *that* employment.

At my leisure I read the English histories and Gascoigne and Chaucer; read again the great Latin poets. And laboured at mine own plays. Many an evening did I forgo the company of my fellows, removed to my chamber, alone with my books, my pen, my ink and paper….

<YHI:> You missed your wife and children.

<WmS:> Such freedom was inspiriting, but, yes, I missed them. I returned most every summer. Quickly the bonds grew strong again. And always the parting would bring fresh pain. There was no help for it.

It seemed that birthing the twins had made my wife barren. We’d have no more children.

My labour began to have its reward. Henslowe agreed to put on Harry the Sixth. And did follow soon Andronicus, Richard the Third, Kate, Petruchio. All the figures I’d dreamt into being, incarnate on the stage. But then disaster struck.

<YHI:> The plague.

<WmS:> Yes. 1592. Just as I was beginning to have this success, they closed the theatres. They were open for only three months in the two years which followed. Players died, writers starved –Greene who’d slandered me most egregiously but who, truth-be-told, had written some not-so-bad entertainments…. Marlowe, that star who shone so bright and briefly in our firmament, that immoderate, open-hearted man –in his art as in his life, –not soon we’ll see *his* like again–… All dead.

I might have followed them, or at least grown utterly impoverished, had I not attracted a most worthy and generous patron, the Lord Southampton. For him I wrote a number of sonnets and to him I dedicated my “Venus and Adonis”, my “Rape of Lucrece”.

<YHI:> Yes, I’ve read them. Quite admirable. The sonnets you speak of…. Were they the ones Thorp printed these five years past?

<WmS:> I had no desire to see them brought to the general view. They were private poems. The Lady Southampton gave them to her husband. ‘Twas he who saw fit to print them. I suspect a number are not being read in the liberal spirit of their writing.

<YHI:> A frowning upon the mistress, you mean.

<WmS:> Yea. I had several., but was nothing prodigal in that regard. I always sent the greater part of what I earned back to my family. And, in truth, at that time I had nothing to give a mistress but a few sweet phrases….

<YHI:> And this particular dark mistress of whom you wrote?

<WmS:> I ask that you not spread this –for I do believe she’s still alive…. She was Aemilia Lanyer, daughter of an Italian musician in the Queen’s court. Quite above her sex in wit and discourse, quite musical….

<YHI:> So the sonnets were addressed to Southampton.

<WmS:> Yes, a fairer young lord you’ve never seen…. My love for him was genuine but also swelled by desperation. I could be jealous, scolding, bold, conspiratorial –but never indifferent….

After the plague had passed we bound together a new company, of which I was a full adventurer, under the protection of Lord Chamberlain Hunsdon.

<YHI:> And the Lord Southampton ceased as your patron.

<WmS:> This new venture promised greater profit. I was thankful to the Lord Southampton for having sheltered me during the storm, but now he was burdened with the forfeit of 5000 pounds for failing to marry Lord Burghley’s grand-daughter — and thus had few ducats to give his poor poets….

What a fine band of fellows we had then! The younger Burbage, Phillips, Heminges, Condell, Sly, Pope, and our boy actors, Nick and Willie … they were brothers … I forget their surname….

And how boldly we put on the plays — A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet…. People flocked to the theatre. But, in the summer of 1596, just as this success began to swell, my son Hamnet, mine only son, having only eleven years, did die.

I’d come to London to raise up our station, that my children might be known as gentlemen. Now no posterity would bear my name…. His pale blue lips would never again speak –or kiss a maid…. ‘Twas too great a burden to bear. Too great, by far….

[<YHI:> I bethought me at this moment he would weep. But he did not.]

That preceding spring I’d renewed my father’s suit to the Heralds’ College for a coat-of-arms. So that autumn, just as the great and chiefest reason for this action –a patent of gentlemanliness for my son and all his sons– ceases to exist, what happens?… Of course, word comes that our suit has been granted….

In the years following I recurred to the History, with my Harry the Fourth and Fifth.

<YHI:> Falstaff! That old rascal….

<WmS:> Yea, Sir John Oldcastle/Falstaff…. Lord Cobham, who was then the Lord Chamberlain and descended of the Oldcastles, asked us to change the name…. The Queen did mightily love Sir John. She was a great lover of the theatre in general. As, of course, was her successor….

In 1597 I bought a spacious house in Stratford. Atonement to my family for the hardship of my absences.

And soon had even more reason for atonement…. I fell in love with a witty and most beautiful woman –what giddy mock-battles we had! What rare, delicious times alone…. Unluckily, she was the wife of a wine-merchant who was, himself, my very good friend…. What a maze of feeling *that* was!…

The year after that, Giles Allen who owned the land the old Shoreditch Theatre stood on became a Puritan and inimical to the theatre. He doubled our rent. Ordinary men might have resigned themselves, but Dick and Cuthbert Burbage were no ordinary men. In the dead of winter they hired a crew –that was the winter of 1598. They took that building down, timber by timber, moved it way across the Thames, used the boards to make the Globe, the largest theatre ever…. That very spring we enacted “Julius Caesar”….

We continued well, but soon were threatened by the children’s companies: St. Paul’s and the Chapel boys. It may seem comical, these nine- and ten-year-olds threatening the livelihood of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, but it was really quite serious…. How fickle the theatre-goers can be!…

I believe we played “Much Ado About Nothing” and “As You Like It” that winter….

Those were the last happy plays I wrote. As I passed my thirty-fifth year, as my father became gravely ill, as it was clear we’d have no more children, as my friend and her husband removed to Oxfordshire, leaving London, I grew serious…. How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable, seemed to me all the uses of this world. From memory’s table all trivial fond records I wiped away. Deep, true things –love, hate, greatness, sorrow– usurped all my time and imagination. “Hamlet” was the play which I wrote then.

<YHI:> Ah, yes, your philosopher-prince, a Dane.

<WmS:> Philosopher with a dagger.

<YHI:> In truth, a very sharp wit.

<WmS:> A dangerously honest wit…. Dangerous to himself, especially.

<YHI:> He speaks some stunning truths…. Did he love Ophelia?

<WmS:> I think he did, but that feeling was overthrown by those for his father and mother and uncle. He changed…. I played Hamlet’s father, the ghost, in those early performances…. It’s easy to get that part wrong: to succumb to an excessive rumbling and quivering of the voice…. There must be no cause, whatsoever, for mirth. The ghost must be deadly serious.

In 1601 my father died, and two years after, the Queen did die. Though King James has not observed and enjoyed the plays so keenly as did Elizabeth, he’s certainly been good to our company: making us his favourites, the “King’s Men”, and inviting us to play at Court more often than all the others put together….

‘Twas near that time Robert Armin replaced Will Kempe as our clown. Not a bad exchange. Kempe was ever the solo player, always calling attention to himself; Armin, a far subtler and more refined actor….

I wrote “The Moor of Venice” then and …

<YHI:> That Iago! I wanted to climb onto the stage and strangle him with mine own hands!… Truly, have you known such men?

<WmS:> I’ve known men of equally evil intent and certainly those of equally great ability but, in truth, none in whom both qualities were combined to such a degree: such an utterly malicious will wedded to so large a mind…. I wouldn’t mind smacking him a time or two myself, me thinks….

In 1606 I finished both “Macbeth” and “King Lear”….

<YHI:> Lear … his cries pierced to my very soul! As he lugged Cordelia about the stage, my heart was like to break….

<WmS:> I’d held Hamnet just so. He was light as a feather….

<YHI:> What a foolish fond old man — giving away his kingdom!…

<WmS:> Remember, he had more than eighty years. It’s only natural that an old man should unburden himself of such workish cares. And Cordelia’s portion needed to be made clear, for her dowry…. No, the fault was not in this divisioning, but rather in having such devilish daughters and requiring the only true one to put her love on show, to hold it up to the crowd….

<YHI:> How beauteously the other strains –Gloucester and his sons, plain-speaking Kent– do harmonize with this one…. Did you learn anything of filial perfidy from your own family?

<WmS:> The perfidy is all in the original chronicle. What I did was to make it tragic: how a great-hearted man is undone by his rash temper, by cruel Fate and his cruel daughters…. Such powerful feelings lie dormant in us all, normally awakened only by birth or death or marriage. But, here, in this world, they never sleep: men live incessantly with their open wounds, with elemental love and hate. The bond of parent to child is Earth’s most potent: the will that the seed should live and grow hath no compare….

The next year my elder daughter Susanna married. We played “Antony and Cleopatra” that summer….

<YHI:> What a grand play! What great figures –“I’m dying, Egypt, dying….”– Mark Antony, Cleopatra, Octavius — veritable Titans! It seemed they’d been everywhere, done everything. They seemed to fill up the whole world!…

<WmS:> Or at least a Globe.

<YHI:> You had good success with it, then?

<WmS:> Yea, very good success…. That winter my brother Edmund who, like myself, had come to London as an actor died. Soon after, my grand-daughter Elizabeth, the only grandchild I’ve had thus far, was born. The summer next, my mother died. We were glad she’d lived to know the child…. I’ve missed her greatly….

<YHI:> If you had to choose from your plays one figure whom your mother most resembled, who would that be?

<WmS:> [Pausing briefly] I suppose Rosalind from “As You Like It”: both being witty, bold, and good-hearted….

We began to play indoors, at the Blackfriars, in the winter. “Pericles” was our first new show there. 1608, I believe it was….

I began to spend more of my days in Stratford and fewer in London. “The Tempest”, which we put on nigh three years past at Whitehall before the King, was the last play I wrote entirely myself.

<YHI:> A most excellent play.

<WmS:> I twice did take the part of Prospero when Burbage was ill:

As if you were dismayed. Be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve;

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. Sir, I am vexed.

Bear with my weakness. My old brain is troubled.

Be not disturbed with my infirmity.

If you be pleased, retire into my cell,

And there repose. A turn or two I’ll walk

To still my beating mind.”

<YHI:> Where is the house?

<WmS:> Near by: Over the great gate into the Blackfriars abutting upon a street leading down to Puddle Wharf on the last part right against the King’s Majesty’s Wardrobe.

<YHI:> How does the Mistress Shakespeare, your daughters and your grand-daughter?

<WmS:> They are well…. Although the first hath of late been strangely given to walking in her sleep: I fear she’ll do herself some harm….

<YHI:> She just began this?

<WmS:> Yes….

Susanna and I and her husband love reading to each other from Ovid and Chaucer; little Elizabeth also attends and doth understand marvellous much — for a child of six!

<YHI:> Do you think you will write any more plays?

<WmS:> I doubt it…. But I thought I was done last year and then was called upon to help with “Henry the Eighth” and “Two Noble Kinsmen”.

<YHI:> I’m curious of your methods…. Take these lines from “Romeo and Juliet”:

Do lace the severing clouds in yonder east.

Night’s candles are burnt out, and jocund day

Stands tiptoe on the misty mountaintops….

<WmS:> ‘Zounds, that was almost twenty years ago! I don’t remember laboring over them excessively…. A couple of minutes, I do suppose.

<YHI:> Yes, no doubt,… a couple minutes….

Do you think your plays will be printed?

<WmS:> Ah, yes, to “preserve them for posterity”…. They belong to the King’s Men, not to me. Why give good scenes to other companies any sooner than we have too?… They may be, eventually….

<YHI:> I think, sir, your words will live forever. A thousand years will only show their increase in the world’s esteem. No poet –ancient, present, or to come– will be accounted your equal.

<WmS:> You honour me greatly,… but ‘twould be quite astonishing if the infancy of English play-making should be its very top. What brave conceits futurity will pen! Our theatre’s like one of those bright Chapel boys — sure to be outdone by his own, maturer self…. As to the ancients, Ovid and Seneca, their work has history’s weight and proof. We are but upstarts….

<YHI:> I can’t agree….

<WmS:> And at the same time I fear suppression of our art.

<YHI:> By the Puritans, you mean.

<WmS:> Yea. In Stratford –like other of the provinces– the Council hath banned all plays these five years past. This zeal *could* spread even to London….

<YHI:> Perhaps. But I doubt that it would last…. Let’s suppose that a king imagines mirrors to be evil and doth decree that they should all be shrouded. They might stay that way for a while, but not for long. We’d pull the curtains aside and peek. Men *will* see themselves…. Plays are the mind’s mirrors…. The shrouds will off!

<WmS:> Let us hope so….

<YHI:> I thank thee for the time which thou hast so graciously here spent with me.

<WmS:> You are most welcome. Fare thee well.

[We departed.]

FINIS.

Shakespeare on the Web:

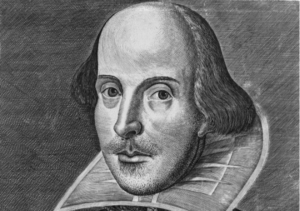

The Droeshout Engraving: First Folio Portrait Page

Copyright © Lucius Furius 2000; last updated, August 2016.